By Abubakar Muhammad Usman

Artificial Intelligence is soon going to be one of the cornerstones in shaping education in Nigeria. AI-guided tutoring and virtual classrooms are increasingly becoming the future.

In Kano State, the government issued a state of emergency in education, made big budgetary promises, and floated deals meant to shake up its schools. But with this political promise comes a grim reality: in many rural schools, promises remain just promises.

- Trump moves to cut more foreign aid, risking shutdown

- Spurs sign Dutch midfielder Simons in boost for new boss Frank

In districts such as Baita, Tsakuwa, and Jili, where some of them are but a mere 30 to 70 kilometers from the state capital, schools still don’t have basic facilities, not to mention the digital hardware or internet access to enable Artificial Intelligence (AI) in learning. Chalkboards and dusty old textbooks are what teachers and students have to contend with, and AI-powered classrooms are still a fantasy.

Ambitious Plans on Paper

Kano State government commitment to transforming its education can be seen on paper. In 2024, it issued a state of emergency in education and went ahead to raise the budgetary allocation for education to 31% in 2025.

Commissioner of Education Ali Haruna Makoda was the mastermind behind releasing more than 1,500 computers to chosen secondary schools alongside solar installations to provide an uninterrupted power supply.

“However we do it, we need to make sure students in these schools can actually use the devices,” Makoda said.

“Committed electricity and the internet are needed if we expect AI to function in our classrooms.”

Governor Abba Kabir Yusuf also reaffirmed the government’s commitment in the long term, confirming six education reform policies, such as the Kano Education Law, 2024, and the Kano Teacher Development Policy, have been tabled before the State Assembly.

“These policies will provide solutions to the challenges in education and enable all the children of Kano to succeed,” he added.

These are included in an overarching suite of new education policies also made up of the Kano Girls’ Education Policy, the Kano State Non-State Schools Policy, and the Gender Policy. Although the Girls’ Education Policy targets better access, retention, and completion of girls, the Teacher Development Policy targets professional development, ethics, and welfare. The Non-State Schools Policy targets standardisation in private schools, and the Gender Policy targets equity and social inclusion in education.

Beyond policies, the state has implemented programs like the Annual School Enrolment Campaign, an Education Emergency Recovery Program, schemes of infrastructure development, and replacing out-of-date education laws over 60 years old to modernize them in response to ongoing needs like security, inclusivity, and incorporating technology.

Organisations such as UNICEF and Adolescent Girls Initiative for Learning and Empowerment (AGILE) have worked in partnership with the state to facilitate ICT integration and girl-child education via scholarships, training, and Conditional Cash Transfer.

The state’s 2023 Annual Operational Plan (AOP), formulated under the Education Sector Strategic and Implementation Plans (2019 and 2022), is a well-defined roadmap towards enhancing equitable access to learning and infrastructure. It divides goals into actionable phases, timelines, roles, and monitoring indicators.

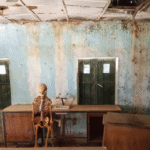

Paper-planned, it’s all there, vision-driven. On the ground in real life, however, it’s a different story altogether.

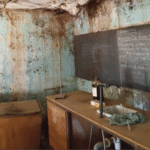

Chalkboards, Not Computers

At Tsakuwa, a town in Dawakin Kudu Local Government Area, 77 kilometers from the city of Kano, the vision of AI in education is utopian. With a population of well over 23,000, the government is finding it challenging to provide even the most basic facilities.

In Government Girls’ Secondary School Tsakuwa, almost 800 pupils are instructed by a mere eight government teachers. The classes are packed, unfurnished, lack , and sanitation facilities. Some sit on the ground; others must share broken tables.

Describing the poor state of facilities in the school, Sani Bala, father of three pupils, said: “Our daughters keep going home because there are no good toilets. Some miss classes altogether because of this problem.”

Due to the government’s slow response, the community banded together and created the Tsakuwa Mufarka Initiative. Headed by Abdullahi Yusuf Wagari, the initiative has employed 20 volunteer teachers and one security officer, each earning ₦10,000 a month through community donations.

“Getting our communities back to school is not an option but a choice we had to make,” Wagari stated.

“Our children cannot wait.”

But despite this grassroots effort, the school still lacks the infrastructure to support even basic computer literacy. Teachers and students have never used an AI tool.

The Role of Inclusive Policy

Experts concur that more funding alone won’t suffice. According to the statistics of the Kano State Senior Secondary Schools Management Board (KSSSMB), Kano has just 826 senior secondary schools, and there is a grave gender imbalance. While 450 are boys’ schools, there are merely 363 girls’ schools.

Rural villages do not have even a single senior secondary school within walking distance. On the other hand, data from the Kano State Private and Voluntary Institutions Board (KSPVIB) list 3,726 private and voluntary schools in the state.

Out of this number, about 42% of the schools exist at the secondary level, which is an estimated 1,565 private and voluntary secondary schools.

The issue of delayed release of funds also falls in its shadow. While there was an expenditure of over ₦13 billion in the first half of 2024, only a meagre ₦1.1 billion was released.

Amina Kasim, the Girls’ Education Coordinator at the Ministry of Education, gave her insight.

“We have not been paid for some of our funded projects since 2023. These delays push everything back, particularly in rural areas.”

Commissioner Makoda insists that there is ongoing work: “We’ve commenced installing solar panels in schools where we distributed computers. Within the next two years, more devices and AI packages will be rolled out to both students and teachers. We’re collaborating with AGILE and UNICEF to avail training as well.”

A Call for Urgent Action

If Kano State is seriously committed to bridging the digital divide and unlocking the potential of AI for education, it has to start by not leaving rural schools behind. That translates into investment in infrastructure, power supply, internet, teacher capacity-building, and offline-enabled digital solutions. It translates into policy being translated into action and acted upon with a sense of urgency.

The Baita, Tsakuwa, and Jili children do not need promises. They need functional classrooms, functioning teachers, and access to the same technologies that are helping their counterparts in private schools to succeed. Without them, the dream of AI in education will be nothing but a dream.

This report was produced with support from the Centre for Journalism Innovation and Development (CJID) and Luminate.